Jackson v. Indiana 406 U.S. 715 (1972)

Theon Jackson, aged 27 years, was a cognitively impaired deaf mute who could not read or write and could communicate only through limited sign language. In May of 1968, he was charged in the criminal court in Marion County, Indiana with two counts of robbery equaling four and five dollars, respectively.

As required by statute, two psychiatrists examined Mr. Jackson concerning his competency to stand trial. They offered testimony concluding that Mr. Jackson’s almost non-existent communication combined with his lack of hearing and limited cognitive ability left him unable to

understand the nature of the charges against him or to participate in his defense. One of the psychiatrists further opined that based upon the interpreter’s limited ability to engage Mr. Jackson, his “prognosis appear[ed] rather dim.”

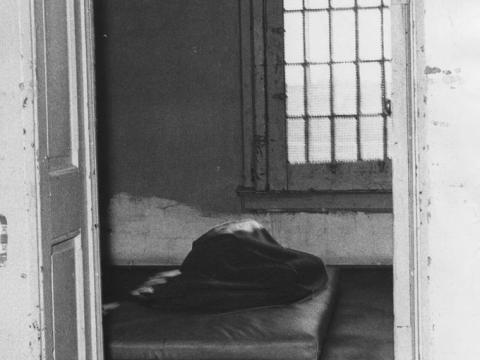

Mr. Jackson was found to be incompetent to stand trial and was committed to the Indiana Department of Mental Health for treatment until he was determined to be “sane.”

His attorney petitioned for a new trial, arguing that there was no evidence that his client was “insane” and that his commitment was paramount to a life sentence without his having been convicted of a crime. The motion was later denied upon appeal to the Supreme Court of Indiana.

In 1971, the Supreme Court of the United States granted certiorari. In reviewing the decisions of the trial court, the Justices concluded that it was unlikely that Mr. Jackson would have met the criteria for being “mentally ill” or “feebleminded” and that, according to both standards, he would likely be eligible for release at any time. However, they observed that his §9-1706a commitment made it unlikely that he would be entitled to release at any time, barring a substantial change for the better in his condition.

Based upon this lack of due process, the Court concluded that Mr. Jackson’s commitment “did not purport to bring into play, indeed did not even consider relevant, any of the articulated bases for exercise of Indiana’s power of indefinite commitment.”

Consequently, the Court concluded: “[a] person charged by a State with a criminal offense who is committed solely on account of his incapacity to proceed to trial cannot be held more than the reasonable period of time necessary to determine whether there is a substantial probability that he will attain that capacity in the foreseeable future. If it is determined that this is not the case, then the State must either institute the customary civil commitment proceeding that would be required to commit indefinitely any other citizen, or release the defendant. Furthermore, even if it is determined that the defendant probably soon will be able to stand trial, his continued commitment must be justified by progress toward that goal.

More Precedents

For more information, please contact Janet I. Warren, DSW, Professor of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, Institute of Psychiatry and Public Policy, University of Virginia, [email protected], or 434-924–8305.